The November Revolution

After the First World War was lost, the Empire came to an end in the November Revolution. In Frankfurt am Main, as in other German cities, workers‘ and soldiers‘ councils were formed. On 9 November 1918, the respective proclamation of the republic was then made by rival Social Democrats and Socialists in Berlin, with the Social Democrats ultimately proving more assertive. A provisional transitional government – also called the »Council of People‘s Deputies« – consisting of the SPD and the USPD (Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany) was formed. The latter decided to elect a national assembly. Free elections were held on 19 January 1919, and women were able to vote for the first time. A parliamentary democracy came into being.

Crisis and stabilisation in the Weimar Republic

The situation for the new democracy was anything but easy. The signing of the Treaty of Versailles, which as a peace treaty after the First World War regulated Germany‘s reparations and cessions of territory to the victorious powers, was heavily blamed on the government. The national right set itself the task of restoring the Volksgemeinschaft of 1914. The political instability of the republic and the social misery since the end of the war were used as a starting point for the propaganda of the völkisch-national parties and groups.

There were also a number of structural problems on the part of the state apparatus. The military, judiciary and administration continued to rely on the old personnel of the empire, most of whom were hostile to the new form of government.

There were many different ideas about how the new republic should be politically organised. The left had split during the November Revolution. For the völkisch and nationalist right in Germany, the November Revolution and its aftermath appeared as Bolshevik and anarchist chaos. They claimed that the defeat of the First World War had been caused by patriot-less sections of the civilian population, which culminated in further conspiracy theories. For example, revolutionaries sometimes from Jewish families would have plunged a dagger into the back of the German people and brought about the overthrow (Dolchstoßlegende). Bolshevism and Judaism were regarded as the main enemies of nationalist circles. Such explanations were increasingly popular among the population.

When the Weimar Republic was unable to pay the reparations, French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr on 11 January 1923. A bloody civil war threatened and the readiness for a putsch and uprising grew within society.

Attempted putsch by the NSDAP

The NSDAP organised an attempted coup in Munich on 8 November 1923. Inspired by Mussolini‘s (leader of the fascist regime in Italy from 1922) »March on Rome«, the NSDAP wanted to realise the »March on Berlin«. However, the attempted coup was crushed the following day and the putschists, including Adolf Hitler, were arrested and imprisoned. Hitler was released six months later, however. The immediate ban on the NSDAP was also lifted in 1925 and the party was refounded.

The national völkisch movement was at a low point at this time. As leader, Hitler secured unrestricted power within the NSDAP. During his imprisonment he had written the first part of his book »Mein Kampf«, which was published in two volumes in 1925 and 1926. In »Mein Kampf« Hitler demanded a »racially pure national community« and the »elimination« of Jews from society. He also propagated the rule of the »Aryan race« over the »Slavic subhumans« of Eastern Europe.

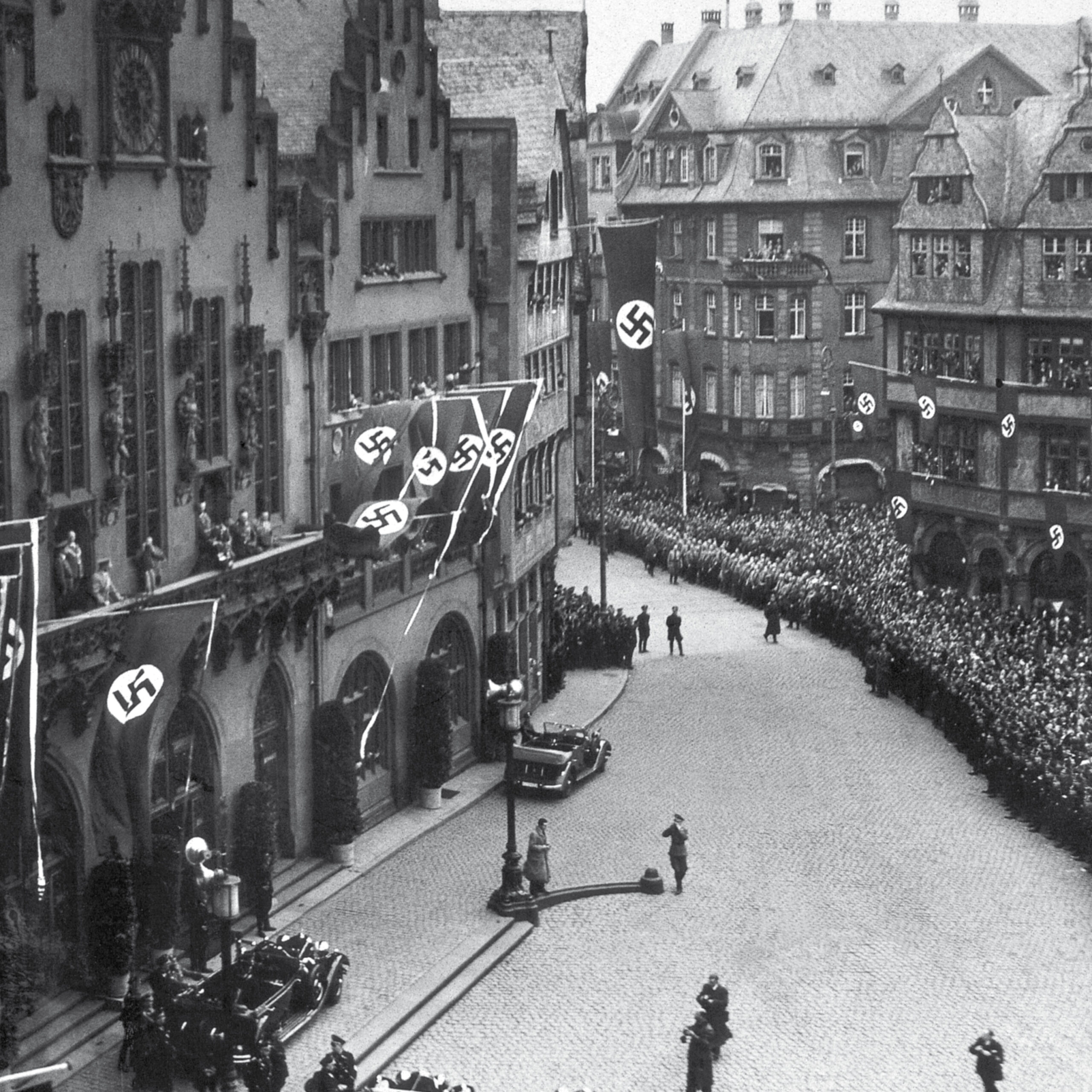

Interim stabilisation and return of the crisis – rise of the NSDAP

Meanwhile, bourgeois cabinets ruled between 1924 and 1928. With the death of the first Reich President Friedrich Ebert, the former Royal Prussian Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg was elected Reich President in 1925. Between 1923 and 1929 there was a reconciliation with the victorious powers and the foreign policy situation increasingly relaxed.

In the course of the world economic crisis from 1929 onwards, the German economy collapsed. At the beginning of 1931 there were five million unemployed in Germany. The social system of the Weimar Republic could not withstand the consequences of the economic crisis. Poverty and hunger characterised the everyday life of broad sections of the population.

The NSDAP developed into a mass movement in the crisis of the parliamentary republic. The effects of the world economic crisis brought the party a strong increase in voters.

Anti-Semitism was an important link between the heterogeneous members of the party. Election propaganda, however, focused on the fight against the Treaty of Versailles and Bolshevism. At the same time, the NSDAP promised to overcome internal divisions and to create a national community.

This was to be realised above all by drawing sharp boundaries, by exclusion and selection. Anti-Semitism played an important role in this concept. The Volksgemeinschaft was to be established through racist exclusion and the policies of the NSDAP were to be enforced through violence.

Left-wing and communist circles tried to fight the strengthening of the NSDAP. But already at the Reichstag elections on 14 September 1930, the NSDAP had a large increase in the number of voters. It openly sought the overthrow of the parliamentary system and entered the Reichstag in 1930 as the second strongest parliamentary group with 107 deputies.

After the collapse of the grand coalition in March 1930, which included the Social Democrats, the Centre and forces of the liberal camp, a state crisis was added to the economic crisis. Even before this, right-wing forces around Hindenburg had begun to push for a shift of power and authority away from parliament and towards presidential power. In addition, from 1930 onwards there were no longer parliamentary majorities for the formation of a workable government. This was followed by so-called presidential cabinets under Brüning, von Papen and Schleicher, all of whom were anti-parliamentary.

In the second Reichstag elections on 31 July 1932, the NSDAP received over 37 per cent of all votes, making it the largest parliamentary group in the Reichstag.

The Sturmabteilung (SA) fought bloody battles with the SPD and the KPD. Hall and street battles were on the agenda. The resistance against the National Socialists grew.

Nevertheless, Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of the Reich on 30 January 1933 at the instigation of the circle around von Papen and Hindenburg. The end of the Weimar Republic was sealed.