The establishment of the police prison on the Klapperfeld as part of the formation of a police apparatus in Frankfurt am Main: The construction of the police prison on the Klapperfeld in 1886 coincided with a period of far-reaching social change that is generally associated with industrialisation, which began intensively in the German-speaking countries in the middle of the 19th century. This change was accompanied by an enormous increase in population and progressive urbanisation, which also had an impact on Frankfurt. These social developments were accompanied by a change in the ruling apparatus. It found its provisional endpoint in the formation of the modern European state with its institutional character and the monopolisation of physical coercion.

The establishment of the police prison and the police headquarters on the Klapperfeld north of the Ost-Zeil, which no longer exist today, were part of the implementation of a modern police apparatus according to the Prussian model, which, historically speaking, can only be traced back for a short time. However, structures emerged relatively early that indicate such a change. In Frankfurt am Main, which became a »free imperial city« in the course of the 13th century, decrees issued by the city council were usually enforced by persons such as the gatekeeper, night watchman or prison guard, who were appointed, if necessary, to intervene in all areas of the public and private life of the inhabitants. From the 14th century onwards, a public penal law became tangible for the first time, which gradually took the place of the atonement procedure aimed at material compensation and reconciliation. The conviction had thus taken root that an institutionalised fine, corporal punishment or even death penalty, which was usually carried out in public, could be a useful means of maintaining »public order«. Yet this means was used extremely selectively – for example, much more frequently against non-citizens than against citizens of the city of Frankfurt.

This selective application of the law, which was tied to the status of certain groups of people, changed in Frankfurt in the meantime with the introduction of the Code Civil and the Code Pénal in 1811 as a result of the conquests under Napoleon Bonaparte. In the course of this, the medieval structure of the police system, in which all police functions were distributed among various functionaries, was replaced by a police body as an independent institution vis-à-vis the internal administration. This was the first time that systematic policing was introduced in Frankfurt, although this development was reversed as a result of the Restoration from 1815 onwards.

In the first half of the 19th century, two decisive events took place in Frankfurt: they provide a revealing insight into the actions of the authorities, which in today‘s understanding would be understood as police tasks. The first was the so-called »Frankfurter Wachensturm« (storming of the Frankfurt guards) in 1833, which was an uprising predominantly carried out by fraternity members, in the course of which the Hauptwache and Konstabler Wache were stormed with the aim of triggering a national revolution. The second occurred in September 1848, when the »National Assembly« meeting in Frankfurt temporarily gave up its claim to Schleswig-Holstein by accepting the Treaty of Malmö. This triggered fierce, völkisch-minded street battles. Both uprisings were put down by military means; this illustrates that maintaining »public order« through repressive measures was not least seen as a military task in the first half of the 19th century.

The same period also saw the almost complete replacement of the instrument of corporal punishment by that of imprisonment. A fundamental difference between these two forms of repression, apart from the supposed civilisation, was above all that both methods dealt with the public factor in opposite ways: Instead of public chastisement aimed at deterrence, the removal of delinquents from the public eye was now considered an effective means against deviant behaviour.

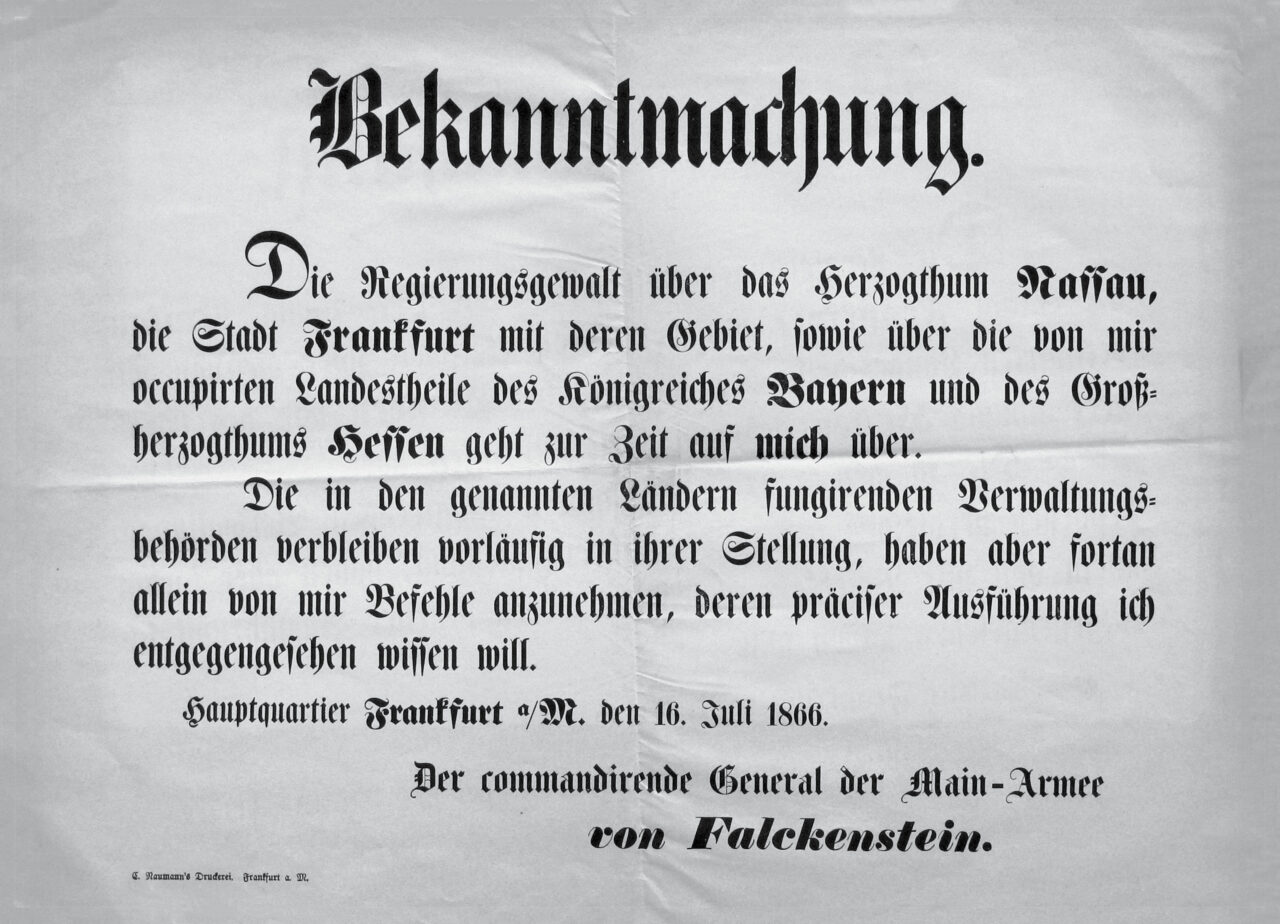

A fundamental change in the situation with regard to a Frankfurt police apparatus then occurred in 1866: In the course of the Prussian-Austrian War, Frankfurt was incorporated into the Prussian state, which was dominated by the military and the civil service. This resulted in a reorganisation of the municipal administration in accordance with the Prussian municipal code. As a result, the police were re-established as an independent organisation, headed by a police chief who was not under the authority of the municipal magistrate but of the royal minister of justice in Wiesbaden.

The centralising developments that resulted from the various wars of expansion led by Prussia culminated in the founding of the German Empire in 1871. They must be seen against the background of the profound social changes already mentioned. Despite the traditionally predominantly middle-class profile of the city of Frankfurt, a proletariat began to form, primarily in the suburbs. The waves of strikes that took place in the Gründerzeit after the concession of freedom of association in 1869 and phenomena such as the ‘horror’ of the Paris Commune of 1871 led to an increase in the fear of the authorities and the bourgeois classes of revolutionary movements.

In Frankfurt, the spectre that was now finally circulating materialised on 21 April 1873 in a so-called ‘beer riot’. When the price of beer, which was regarded by the working classes as a basic foodstuff, was raised by the breweries from 4 to 4½ Kreuzer, violent riots broke out on the non-working last day of the Spring Fair (popularly known in Frankfurt as “Nickelchestag”). The municipal police with its 52 constables were completely overwhelmed by this situation, which once again resulted in the deployment of the military. According to official figures, 18 people lost their lives as a result.

This event, which constituted the largest riot in Frankfurt between 1848 and 1918, was not unique in the entire German-speaking world. Because of this and the growing impression of an acute class struggle in all political camps, the ruling classes of Prussia came to the conclusion that a systematic expansion of the police apparatus was necessary. What is striking here is the clear motivation to suppress possible attempts at subversion and the strong emphasis on the political police, which played a major role especially in the implementation of the Socialist Laws from 1878 onwards. After the expansion in Berlin and the cities of the Ruhr region was already in full swing, it also came to bear in Frankfurt in the course of the 1870s. Here the so-called “Schutzmannschaft” was expanded in terms of numbers, and a police headquarters was built directly on the new Zeil and behind it the police prison on the Klapperfeld. Until then, the police had still relied on municipal facilities.

Under the capitalist conditions of high industrialisation, there was an obvious internal rearmament on the part of the state towards its ‘subjects’. That this was by no means a limited development is made clear above all by the fact that 28 years after the completion of the police headquarters on Klapperfeld, a new one was moved into on Hohenzollernplatz, whereby further ‘use’ was to be found for the prison on the original site for over a century.