The construction of the prison on the Klapperfeld and the system of detention

Even before the construction of the former police prison, plans were made to build a prison on the Klapperfeld site. However, with the reorganisation of the municipal administration in the wake of Frankfurt’s annexation by Prussia in 1866 and the urban expansion during this time, this plan is not implemented. From 1882, construction of a prison is begun on the site of today’s JVA Frankfurt-Preungesheim.

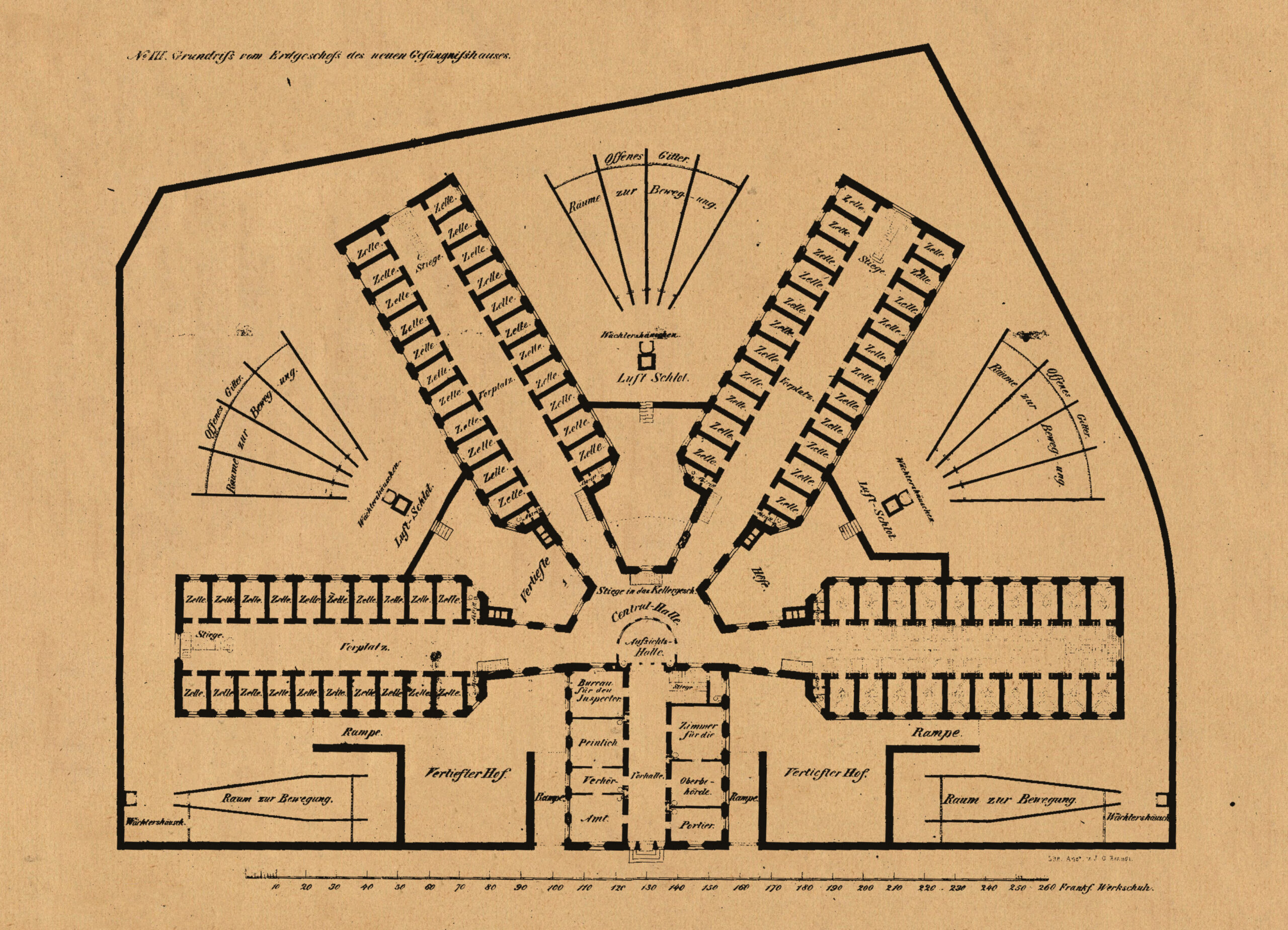

In the free imperial city that existed until 1866, prison construction was the task of the municipal administration. It was therefore officials from the municipal building department who were involved in the planning of a ‘cellular prison’ on the Klapperfeld. Two reports by the building authority on the planning from 1838 and 1861 show that the planning of prison buildings was based on certain ideas of a social order, which was reflected in a certain architecture of the prison, as can also be seen in the construction of the former police prison Klapperfeld.

The building commission of 1838 took its cue from the new English prison buildings, which were considered the most modern in Europe at the time. They manifested a new order of imprisonment. Since early industrialisation, imprisonment, combined with forced labour, began to replace the corporal punishment that had been used until then. But it was not until the beginning of the 19th century that imprisonment became established as a general means of state repression in most European states. In English prison buildings, the system of solitary confinement was applied from the 1840s onwards:

»The system requires:

(1) That each individual prisoner be confined by day and by night in a separate prison room, which shall be light, thoroughly ventilated and heated, and of proper size to permit the prisoner to exercise himself and spend a part of his time in strenuous manual labour.

(2) That the construction of these cells prevent any communication with each other, and that to this end the partitions be of such thickness, and other precautions be taken, that any communication be so impeded that any temptation to undertake it must cease.

(3) That the cells be provided with a water supply for washing with a water closet, with service pipes, so that there can be no occasion for the prisoner to leave his cells until he receives instructions to do so, but that he at the same time have the means in his power to give the officials notice of his wish to see them in case of illness or other urgent occasions.

(4) That there be not only opportunity for general supervision and inspection, but also that each individual prisoner may be supervised without observation. And since it is an essential part of the system that each individual should have frequent communication with one or other prison officer during the course of the day, the easiest possible access to every part of the building to each individual cell is highly desirable.

(5) So that the unity of the system is not interrupted by the permitted gathering of prisoners for worship or instruction, it is essential that the chapel be provided with special chairs, and that, so that it is not necessary to allow prisoners to come together when they are enjoying free air, separate courtyards be set up for this purpose.«

Unlike the previously existing forms of imprisonment in the penitentiary, in which prisoners are locked up together and forced to do work, solitary confinement aims to isolate prisoners. Separating prisoners from social contact and all sensory perceptions outside the cell was intended to intensify the effects of imprisonment. The work they had to do, just as in the penitentiary, did not serve to qualify the prisoners. Their real purpose was the physical exertion involved. It was part of the punishment.

According to the ideas of the penal theorists who advocated solitary confinement, it was intended to adapt prisoners to a ‘regulated life’ in bourgeois society. The prison cell as a forcible relegation to solitude was thereby understood as a positive educational instrument according to the bourgeois ideal of the human being who independently copes with every life situation.

Locked up in the cell, however, the prisoners are externally determined in almost all matters. They are forced into a relationship of obedience with the prison staff. This presupposes that the prisoners are aware that they are under constant observation during their stay in the cell. Prison cells are therefore built in such a way that the entire cell can be viewed unnoticed from a point at the door at any time.

The principle of this surveillance method goes back to the design of a prison building by the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham: the Panopticon.

.

annexation of Frankfurt by Prussia in 1866 and the urban expansion during this period. (Source: Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main)

In a modified form, it can also be found in the construction plan for a prison that was to be built on the Klapperfeld from 1838. Unlike the police prison, this building was divided into several cell wings arranged radially around a central hall. All cell doors were to be visible from an observation point located inside. This did not allow for direct control of the prisoners in the cells, but for monitoring the entire prison operation and the work of the guards.

In a further draft by a commission of the Frankfurt building authority from 1861, no fundamental changes were made to the prison plans. In addition, however, there is the emphatic reference to dividing the prisoners into categories and separating them according to the status of their conviction and according to gender. This principle also underlies the construction of the Klapperfeld police prison.

The construction of the Klapperfeld

The construction of the detention cells in the Klapperfeld follows the same principle of detention as in the planned prison buildings of the mid-19th century. For the repression exercised on the prisoners, the architecture of the cell was always only one means among others. Nevertheless, its unchanged existence during the more than 115-year history of the Klapperfeld as a police prison is remarkable.

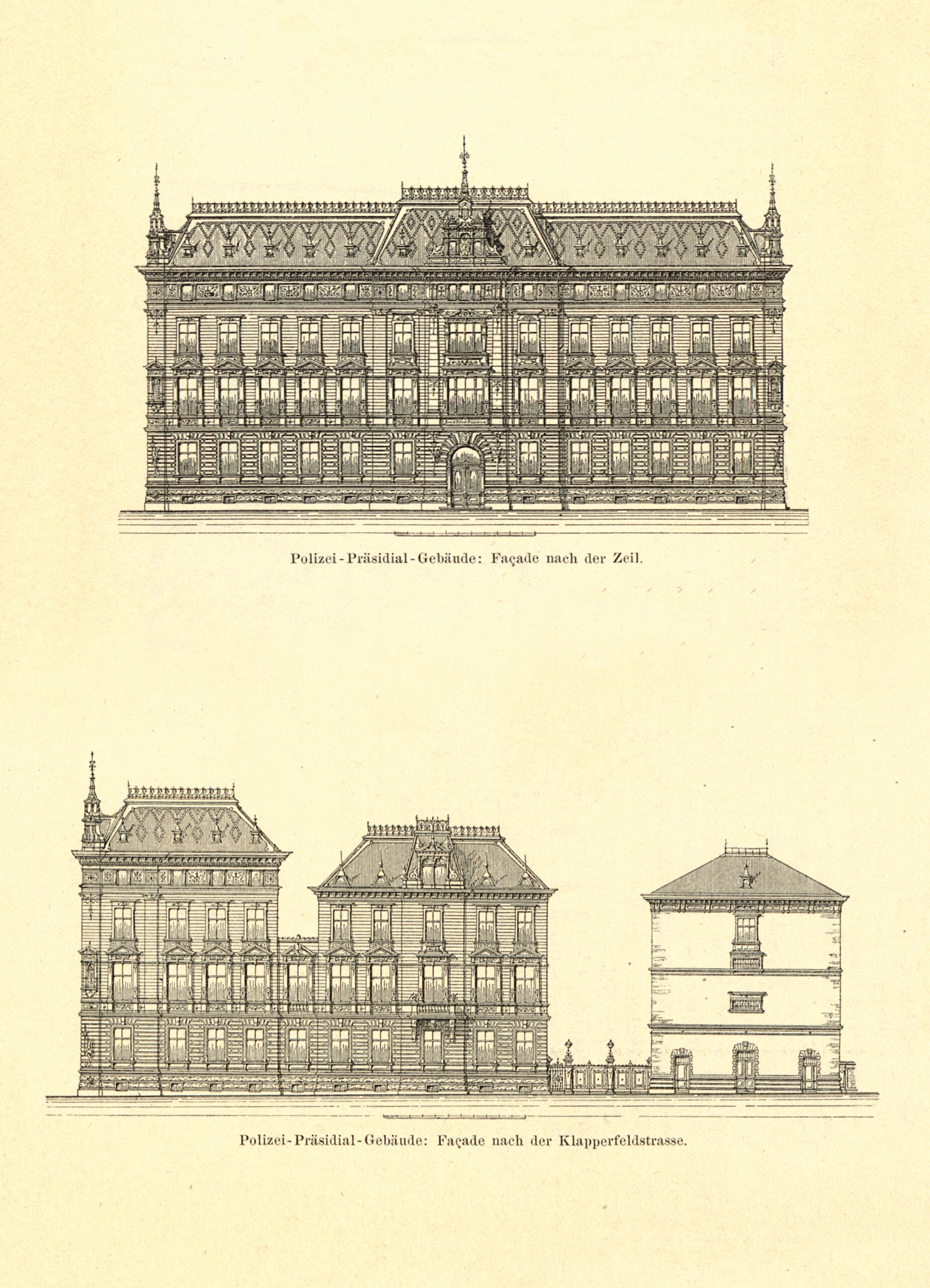

The former police prison was built from 1884 onwards according to a design by the Frankfurt city architect Gustav Behnke. It was completed in 1886 under the direction of the Prussian government master builder Temor. The four-storey building consisted of an administrative wing and a cell wing. On the top floor of the administration wing was a flat for the director of the prison. The cell wing and the courtyards in front of the prison were divided vertically into a “men’s section” and a “women’s section”. In both sections there were a number of detention rooms which served to confine prisoners. On the ground floor of the administrative wing were rooms for a doctor. There was also a separate building on the “Weiberhof” where prostitutes were examined by a police doctor.

The function of the doctor was fundamental to the operation of the police prison. His main task was not to care for ‘sick’ prisoners, but to carry out medical examinations, even against the prisoners’ will. Finally, prisoners were also locked up in separate cells after medical judgements by the police doctor.

Source: Institut für Stadtgeschichte: Bestand: Impressen Signatur: 143 (S. 104f)