Contact with the outside world was only possible for Klapperfeld inmates with special permission. Only rarely was it possible to smuggle messages past the prison staff, thanks to particularly clever ideas from inmates and relatives. Another chance came when guards showed a spark of humanity and turned a blind eye.

There was an opportunity for this twice a week, when relatives were allowed to bring fresh laundry and pick up used clothes. However, permission from the Gestapo was also required for this.

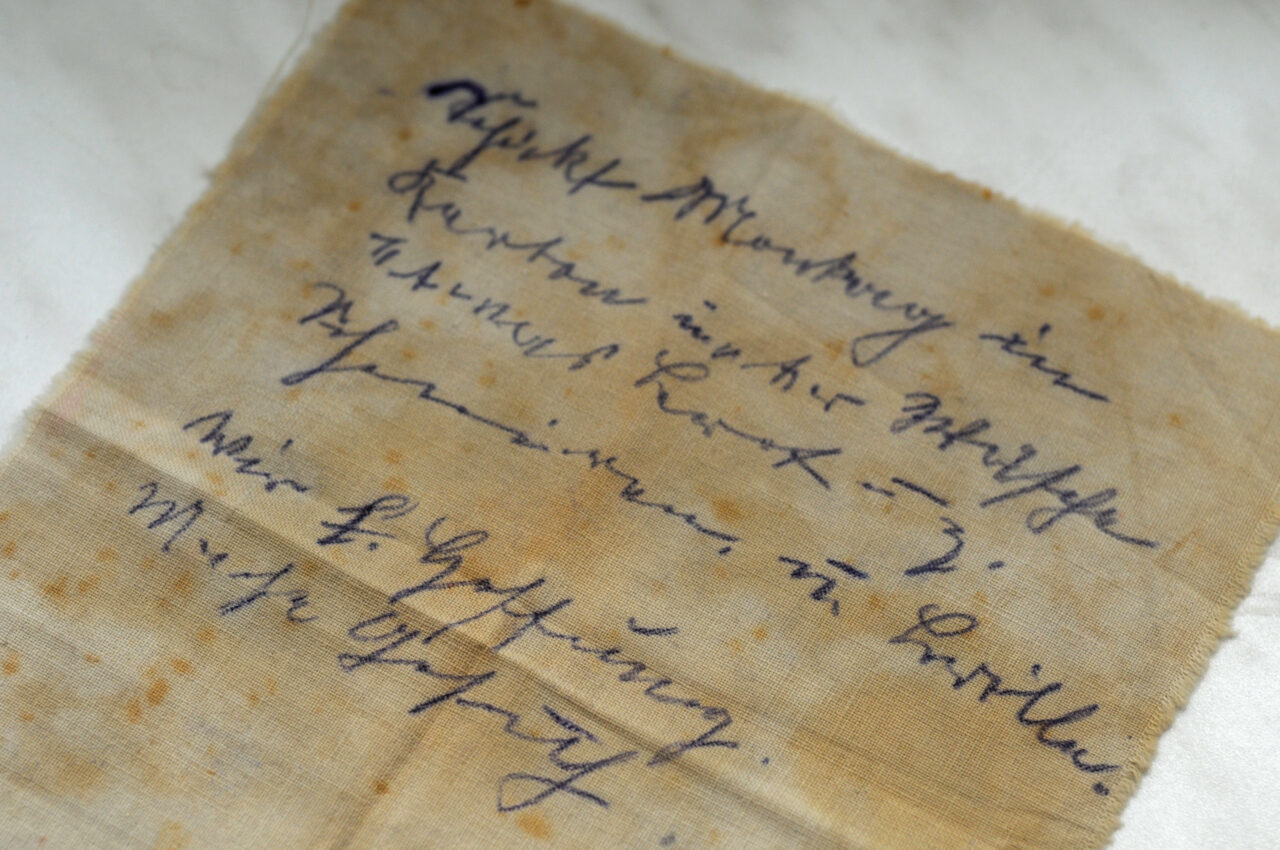

Examples of methods of message transmission that the guards were not supposed to notice were sewing messages into the hem of laundry, carving messages into soap or hiding them in toothpaste tubes.

Through a note written on toilet paper to her husband and son, which a woman arrested around 24 February was able to smuggle out of the police prison, her relatives learned the following about her further progress:

»My dear Karl and Hansel! These are the last lines I am writing to you. Today I signed the camp note along with many others. Today it is also eight weeks that I have been here. We are probably going to Auschwitz near Katowice in Upper Silesia. Keep me dear, stay faithful to me, I will try everything to hold out. No matter how hard the work is, I will do everything to preserve my life, because I want to and must come to you again. My punishment is disorderly conduct at [the municipal Gestapo representative] Holland, where you yourself were present and I would have disguised myself and not identified myself as a Jew and [it] would endanger the Jewish law. Basically, it‘s an action. You can‘t help being born a Jew. The transport is bad, through many prisons until one is in place. But even that has to be endured. If you don‘t get a sign of life from me, I must not write, I am always with you in my thoughts and never forget you. [ … ] Now stay healthy and do not forget me, dear Hansel, remain faithful to the Father and may God grant that we may still spend our old age together. Many thousands of intimate greetings and kisses from your deeply sad mother, who is always thinking of you.«

Many relatives roamed around the prison, especially in the evening hours, trying to show the prisoners that they were there by whistling or singing. If there were no guards, the prisoners sometimes managed to respond in an appropriate way.

Another meeting place for relatives was Frankfurt‘s main railway station, as it quickly became known when deportations were taking place. Thus, attempts were made to see the arrested relatives, who were escorted to the trains with dogs and often kicked, one last time.

Sources: Monica Kingreen: »Die Aktion zur kalten Erledigung der Mischehen« – die reichsweit singuläre systematische Verschleppung und Ermordung jüdischer Mischehepartner im NSDAP – Gau Hessen – Nassau 1942/1943. In: Norbert Kampe/Peter Klein (Hg.): NS-Gewaltherrschaft. Beiträge zur historischen Forschung und juristischen Aufarbeitung. | Monica Kingreen: Die Verschleppung und Ermordung hessischer »nichtarischer« Christen. In: Hermann Düringer/Hartmut Schmidt (Hg.): Kirche und ihr Umgang mit Christen jüdischer Herkunft während der NS-Zeit – dem Vergessen ein Ende machen. | Elsie Kühn-Leitz: Mut zur Menschlichkeit. Vom Wirken einer Frau in ihrer Zeit. Dokumente, Briefe und Berichte. Hrsg. von Klaus Otto Nass. Bonn 1994. | Monica Kingreen (Hg.): »Nach der Kristallnacht«. Jüdisches Leben und antijüdische Politik in Frankfurt am Main 1938-1945. | Abschrift des Kassibers von Martha Rammler, HHstA Wiesbaden, Abt. 461-37048/3 Bl. 786.